by Tony Rinaudo

Where natural resource management principles are applied, there is “resource expansion” – more fodder, more grain, more fuel wood, more water. These principles, including Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR) directly contribute to a reduction in conflict. Afterall, if there is enough to go around – why bother fighting?

I hear countless stories of conflict between herders and farmers. These conflicts usually revolve around increasing competition for shrinking resources due to land and vegetation degradation and the reduced availability of water. The extent and severity of degradation is alarming! Up to two thirds of the productive land area in Sub-Saharan Africa is reported to be affected by land degradation[1], and climate change is making things worse – the percentage of the earth’s land stricken by serious drought doubled from the 1970s to the early 2000s[2].

Pastor James Wuye from Kaduna, Nigeria is actively involved in peace building between conflicting groups. He claims that stability across the middle belt of Nigeria depends on ecology.

“If we don’t reverse the loss of trees in this area over the next 10 years, we will have catastrophe. Evergreening is the biggest solution to security. There are five tree species that serve as fodder for cattle and can be used as trees for peace between herders and farmers. If we give back to the land, the land will give back to us”, Pastor Wuye said.

Working towards a common goal of building prosperity and well-being through restoration of natural resources is a powerful prophylactic to conflict.

When you share a natural resource base upon which livelihoods depend, such as land, vegetation, water and biodiversity, it is essential to have mutually agreed upon by-laws. Such laws lay out how natural resources will be sustainably managed and equitably utilized, by whom and when. They should come with a control mechanism so that non-compliance can be dealt with fairly and transparently. This works best when the community agrees on the by-laws and then collaborates with local government for enforcement. Good FMNR programs bring diverse stakeholders together to work towards achieving these common goals through sustainable natural resource management. Such programs are connectorsin peace building parlance – things conflicting parties have in common.

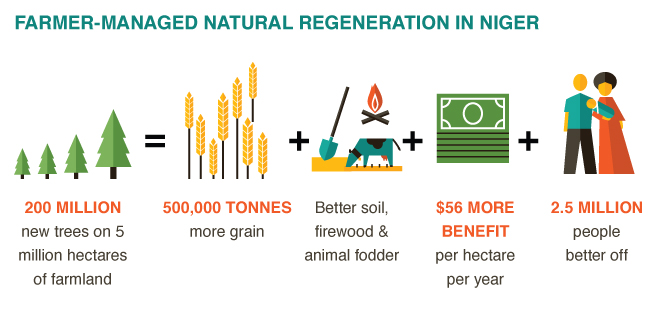

In Niger Republic, where FMNR has spread exponentially since the mid 1980’s, it is estimated that cereal yields have doubled[3]. Farmers now produce an additional 500,000 tons of cereal per year compared to the 1970s and 1980s. As a result, 2.5 million people have become more food secure[4]. The added gross income from FMNR is in the order of $900 million per year[5],which benefits more than 900,000 households – this equates to 4.5 million people.

This can only have had a positive impact on conflict reduction. In an unpublished report[6], the number of incidences of conflict between herders and farmers in districts of Niger which had embraced FMNR had plummeted by 70%.

My observations

In March 2019, I had the privilege of revisiting Niger. My observation, twenty years after leaving Niger, is that vulnerability to environmental shocks, such as drought, windstorm and insect attack, has greatly reduced because of FMNR adoption.

A virtuous cycle was observed. More trees in the landscape and less use of fire, has resulted in more available fodder, allowing increasing livestock numbers, extending even to free range poultry grazing. This in turn produces food security and income, more fuelwood and building timber, more wild foods and traditional medicines.

Fig 1. Typical farmland in Niger in early 1980’s barely supported life in any form during the dry season.

Fig. 2 More trees and shrubs, along with reduced incidence of fire and removal of crop residues, has resulted in more fodder available for livestock. Farmers have benefited from an increased livestock carrying capac

FMNR has provided a foundation for agricultural diversification. Some farmers have greatly increasing their income from honey, grafted zyzyphus, poultry and livestock. Also noted were introduction crops which have not been grown in the region for decades, including sesame, cassava and sweet potato.

Soil has increased in fertility and has greater water holding capacity. This can be attributed to more organic metter from leaf litter , increased microbial activity, the incorporation of more crop residues into the soil and increased manure from animals and birds seeking shade. The result has been increased grain yields, along with greater resilience against crop failure, even in years of lower rainfall and seasons with long dry spells between rains.

Fig. 3: Yahouza Harouna grows sweet potato as a second crop intercropped with millet – an innovation perhaps only possible because of increased soil fertility and moisture holding capacity due to increased tree cover.

But of course, FMNR, along with all of natural resources management is only one leg of the stool. Building peace also requires three further courses of action –

- Economic development initiatives – desperation often drives conflict. Restoring landscapes provides a platform for economic development, but to make money from it requires intentionality. This can be achieved by developing value chains, giving quality assurance, and opening markets, amongst others.

- Building leadership capacity – leadership and creation, or the strengthening of existing organizational structures, such as cooperatives and development groups, are important to the peace process.

- Proactive peace measures to bring opposing sides together – this involves measures such as dialogue and social events.

It is sad to see the tragic loss of life and destruction of property caused by extremist groups around the world. One can only hope that fewer youth would be drawn to join their ranks when they can create a dignified living on their own land.

Existing blogs on conflict that can be drawn from or referred to.

http://fmnrhub.com.au/conflict-resolution-sustainable-management-trees-ghana/#.V9_EEMtMrIU

http://fmnrhub.com.au/milk-honey-deal-rwanda/#.V9_EL8tMrIU

http://fmnrhub.com.au/fmnr-reconciliation-trees-rwanda/#.V9_EQctMrIU

[1]www.dry-net.orgJune 2013.

[2]http://drylandsystems.cgiar.org/news-opinions/trillions-dollars-worth-natures-benefits-lost-annually-due-land-degradation#sthash.Xwk4fZmn.dpuf

[3]Pye-Smith.C. 2013. The Quiet Revolution: How Niger’s farmers are re-greening the parklands of the Sahel; ICRAF Trees for Change no.12. Nairobi; World Agroforestry Centre.

[4]Reij, C., Tappan, G., Smale, M. 2009. Agro-environmental transformation in the Sahel: another kind of “Green Revolution”. IFPRI Discussion Paper 00914. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington DC

[5]Sendzimir, J., Reij, C.P., Magnuszewski, P. 2011. Rebuilding Resilience in the Sahel: Regreening in the Maradi and Zinder Regions of Niger Ecology and Society 16 (3): 1 http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol16/iss3/art1/